The X-Men have their share of mutants whose powers make them unattractive, but there’s a troubling trend of these characters being “fixed” and becoming traditionally good-looking. Not only does this do a disservice to the characters, but it also does one to the central metaphors of mutant oppression.

The concept of visible mutants has been a key one to the X-Men for a long time. By introducing mutants with a visible mutation, characters exist whose mutation can never be forgotten by them or the outside world, such as Nightcrawler, introduced in Giant-Size X-Men #1 by Len Wein and Dave Cockrum fleeing from an angry mob. Even more important is the existence of visible “ugly” mutants, whose appearance makes them unable to participate normally in human society. Key examples include Callisto and Marrow from the Morlocks, a community of non-passing mutants. Grant Morrison’s run on New X-Men also introduced Beak and Angel Salvadore, whose physical mutations in that run made them self-loathing. However, these appearances often don’t stick.

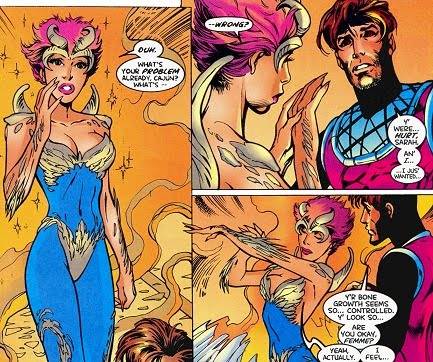

Mutants who are visibly “ugly” are often later transformed into more conventionally attractive forms, to the detriment of what their original appearances meant to their stories and character. During New Warriors vol. 4 by Kevin Grevioux, readers are re-introduced to Angel and Beak, both of whom lost their powers during the decimation, when the Scarlet Witch de-powered the vast majority of mutants on Earth. In contrast to their previous appearances, they now appear as conventionally attractive after their de-powering. Similarly, in X-Men vol. 2 #90 by Alan Davis and Terry Cavanagh, Marrow is transformed into a more traditionally feminine form, which leads her to begin to soften as a person as well. In both these cases, the story either explicitly or implicitly suggests that the characters have in someway been “fixed” by becoming more conventionally attractive. These changes not only erase the internal character struggles of the characters in question, making them less interesting, but also suggests that not being attractive is inherently a bad thing.

One example of a transformation that crucially bucks this trend is that of Callisto. Callisto is presented as someone who has ownership over her scarred face and body. In Uncanny X-Men #259 by Chris Claremont and Mark Silvestri, Callisto is attacked by fellow Morlock Masque, who uses his ability to reshape flesh to “fix” Callisto’s face, giving her the appearance of a supermodel. Callisto, in contrast to the other characters who’ve been transformed, hates being made beautiful. Her scarred appearance was one that she had taken ownership of and found pride in. By subverting the expectation of beauty being desirable, Chris Claremont shows just how narrow-minded the idea that beautifying someone is fixing them is.

Beautifying characters also breaks the metaphors of mutant oppression. It’s the outside world that tells mutants that they’re “broken” or “ugly,” it’s not any sort of objective truth. While characters such as Angel and Beak explicitly struggle with their mutation in Morrison’s run, it doesn’t mean they can’t take ownership of it. Metaphorically, this intersects with the Radical Model of disability politics, the idea that someone with a disability is not “broken,” but rather that they are simply different and diverse. This model puts the onus on the larger world to step up and accommodate for the person with a disability, not the other way around. In X-Men terms, Beak and Angel shouldn’t have to be physically attractive to have value, their value is inherent regardless. This is how the X-Men should view being “fixed,” it’s not them who need to change, but the world that needs to.